This blog represents an exploration of ideas and issues related to what it means to be a disciple of Jesus in the 21st century Western context of religious pluralism, post-Christendom, and late modernity. Blog posts reflect a practical theology and Christian spirituality that results from the nexus of theology in dialogue with culture.

Saturday, August 26, 2006

Off to Burning Man

Thursday, August 24, 2006

Simulation and Pseudo-Events: Travelers or Tourists in Culture and Spirituality

Yesterday was the first day of the new semester for seminary. During chapel the president, Dr. Don McCullough, presented a message that was interesting not only in the application he drew, but also in applications in other contexts.

Don’s devotional presentation touched on the topic of the early disciples and what it meant to follow Jesus. Of course, McCullough read a New Testament passage as his point of departure, but then referenced the book The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America by Daniel Boorstin (Vintage; Reissue edition 1992). Boorstin is a historian who, in this book, developed the idea of simulation as a social category. The main thesis of the book is that Americans live in an “age of contrivance” and that our public lives are filled with various “pseudo-events” or “artificial products” that simulate reality and which leave the individual who experiences the events or utilizes the products feeling as if they have experienced reality when in fact they have had their stereotypes confirmed by an encounter with the simulation. Although this book was first published in 1961, Boorstin’s cultural analysis might be considered somewhat prescient if not prophetic.

During the chapel devotion McCullough focused in on chapter three of Boorstin’s book, “From Traveler to Tourist: The Lost Art of Traveling.” In this chapter Boorstin notes the etymological connection between the words “travel” and “travail.” In the not-so-distant past travel was a dangerous experience that exposed the traveler to various hazards such as the mode of traveling (consider cross-Atlantic seafaring), disease, robbery and the like. In the past a traveler would literally experience travail if she wanted to experience another culture. There was a cost and great personal investment in the process.

Today, of course, travel is very different. It is possible to leave the comforts of home and get on a train or jet with controlled climate, good food, and entertainment and travel around the world, only to check in to a hotel with all the comforts of home in establishments catering to the desires of pampered Americans and other Westerners. Little travail often accompanies modern travel.

Beyond this, travelers today are more often tourists, crossing land and sea ostensibly to experience another culture, but instead they encounter a series of pseudo-events, simulations of culture that conform to the expectations and stereotypes of the tourist.

McCullough applied this concept to Christians and their spiritual journey with Jesus. Are they following the difficult path of the traveler who willingly experienced travail, or are they the modern tourist content with a pseudo-event and a pre-packaged discipleship experience?

As I reflected on these ideas I thought of other applications in terms of our understandings and sojourn. First, in our American and broader Western contexts, does our understanding of the various subcultures and their spiritualities reflect the complex and messy realities of the subcultures themselves, or is our understanding really a pseudo-culture and pseudo-religion, an oversimplified and reified image that conforms to our evangelical presuppositions that then become all too easy to dismiss and demonize? And second, in terms of our spiritual sojourn, are evangelicals willing to walk the difficult path of the traveler rather than the tourist, not only in terms of our own spiritual journey with Christ, but also to come alongside other spiritual travelers on differing paths? Or perhaps we’re more spiritual tourists, content with the prepackaged simulations of what we think other people’s spiritual journeys are all about?

Image source: http://www.polyu.edu.hk/~or/photo/Artificial%20eye%202.jpg

Monday, August 21, 2006

Dance, Festivity, Christianity, and Burning Man

I am still reading through and reflecting on The Feast of Fools: A Theological Essay on Festivity by Harvey Cox (Harper Colophon Books, 1969) for its application to understanding cultures and festivity, particularly as it relates to spirituality in Christianity in late modernity. Chapter three is titled "A Dance Before the Lord," and in this chapter Cox includes a quote that caught my eye:

"A people who dance before their gods are generally freer and less repressed than a people who cannot."

Cox notes that dance within expressions of worship has a long history in Christianity, going back to the Old Testament. He reminds us of the "widespread use of dance not only in pre-Christian and pagan religions but in the Christian church itself. While I have not finished this chapter, I have found the ideas in it thus far thought provoking, especially in light of my upcoming attendance at Burning Man where dance and the celebration of the body are valued in this artistic community. The relationship between issues of the body and its connection to spirituality have also been in my mind in my interaction with various Pagan and Gnostic websites where Christianity is critiqued for its attitudes toward the body. Cox's conclusion in this chapter is worth reflecting on in this regard:

"What eventually happens to the church or to liturgical dancing is not a matter of urgent concern in itself. What happens to our stifled, sensually numbed culture is important. To reclaim the body, with all its earthly exquisiteness in worship is a hopeful sign only if it means we are ready to put away our deodorants and prickliness and welcome the body's smell and feel back into our ascetic cultural consciousness. Only when that happens will we know that our civilization has left behind the gnostics and their wan successors and has moved to a period when once again we can talk about the redemption of the body without embarassment."

Image source: http://www.moonski.net/burningman/burningman/art/dance.jpg

Emergent Mormon Village?: When Satire Misses the Mark

Burning Man: Experience Leads Pastor to Redefine Weird

1. I no longer find it weird that Burning Man thrives in a harsh setting with no advertising budget.

2. I do find it weird that the church strives to convenience people when people really thrive on challenge.

3. I no longer find it weird when people express themselves in ways I never thought of.

4. I find it weird that the church world appears to have been made from a cookie cutter.

5. I no longer find it weird that people will go to great lengths to escape their reality.

6. I find it weird that so many Christians are satisfied with their present reality.

Read the article to find the context for these conclusions, and how Pastor Bohlender came to these ideas.

Saturday, August 19, 2006

Perspectives on the Sacramento LDS Temple

My friend and colleague, John Smulo, Lead Pastor of LifeSong Church, has posted his article on the temple opening, and readers might also find the comments of interest from varying perspectives from those in the community.

Image Source: The Sacramento Bee

Thursday, August 17, 2006

Pew Forum and Islam in the West

The first is a story of cooperation between two unlikely parties, Muslims and Mormons, working together to provide humanitarian aid in the Middle East as a result of the fallout from the war between Israel and Hezbollah. If such divergetnt religious groups as Muslims and Mormons can come together to meet human need then perhaps there's hope for Mormons and evangelicals doing the same.

The second item is an interview in response to a recent Pew Forum Survey:

On July 7, 2006, the Pew Global Attitudes Project released an international survey focusing on Muslim and Western perceptions of each other and on the Muslim experience in Europe. The poll surveyed more than 14,000 people in 13 nations: India, Egypt, Indonesia, Jordan, Nigeria, Pakistan, Russia, Turkey, the United States, Britain, France, Germany and Spain. A survey of Muslim populations in the four European countries was conducted in partnership with the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life.

In a wide-ranging interview at the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, Amaney Jamal, assistant professor in the department of politics at Princeton University and a specialist in the study of Muslim public opinion, commented on the survey's findings and their implications. Jamal is also a senior advisor for a Pew Research Center project on a comprehensive study of the views and attitudes of Muslim Americans. The Forum is a partner in this year-long survey project, which will be completed by next summer.

In the interview, Jamal discusses, among other things, the negative perceptions Westerners and Muslims have of each other, the role of the media in perpetuating stereotypes and what the findings mean for U.S. foreign policy.

Chas Clifton and a Pagan Writer's Blog

I monitor the referral sites for my blog through Extreme Tracking and noted that a few hits came from Mr. Clifton's blog, Letter From Hard Scrabble Creek. These come from two entries, one commenting on Sacred Tribes, the e-journal I co-edit, and the other commenting on my post on Morwics, the Pagan-Mormon synthesis in Utah. Thoughtful evangelical readers interested in Pagan studies might appreciate reviewing Clifton's comments. But please, no proselytizing and no rude comments. Let's try to apply the Golden Rule to interreligious or interspiritual dialogue: Blog unto others as you would have them blog unto you.

Wednesday, August 16, 2006

Forbidden Faith: The Continuing Gnostic Legacy

I recently went to my local library to pick up a couple of books on the changes in American spirituality from that associated with institutionalism and place to that of a personal quest orientation. As I was leaving, the library display of books caught my eye. It was a collection of books associated with The Da Vinci Code, but a book on Gnosticism engaged my curiosity. I ended up checking it out, Richard Smoley's Forbidden Faith: The Gnostic Legacy From the Gospels to the Da Vinci Code (HarperSanFrancisco, 2006). The dust jacket for the book describes Smoley as the editor of Gnosis magazine, and co-author of or author of several books on esotericism and "inner Christianity."

Smoley writes in popular fashion and provides an overview of the history and varieties of Gnostic thought. He looks not only at ancient forms of Gnosticism but also traces it to more recent times in what he calls the "Gnostic Revival." This chapter, along with Gnosis and Modernity, and The Future of Gnosis, represent some of the more interesting treatments as he traces neo-Gnostic elements in various facets American culture, including pop culture as exemplified by The Matrix films and The Da Vinci Code.

It should come as no surprise to either traditional Christians or those supportive of various forms of neo-Gnosticism that I disagreed with portions of his book, particularly his discussion of the canonical Gospels and his claim that none of them were written by eyewitnesses. Smoley also speculates that the Gnostic Gospel of Thomas might indeed be dated earlier than the second century due to its alleged resemblances to the hypothetical Q document, and therefore it might be the first gospel and represent some of the earliest expressions of the faith of the early Christian communities. A blog is not the place to rehash these debates, but suffice it to say I believe the weight of scholarship runs counter to Smoley's claims. Hopefully traditional and "inner Christians" can continue to not only debate but also to discuss our differing views in these areas.

The book also includes other troubling areas when Smoley describes the evangelical emphasis on a personal relationship with Christ as little more than a mental construct that represents a relationship with an imaginary friend. But before evangelicals get too upset we need to consider Smoley's reminder that, "As harsh as this characterization may sound, it is in many ways milder than the accusations flung by many evangelical Christians at the spiritual experiences of others, which (insofar as they are granted any reality at all) are frequently dismissed as delusions engendered by demons."

Despite these disagreements, traditional Christians should take note of several items in this book. For example, Smoley touches on the shortcomings of Christian clergy that reveals problems in the education and contemporary cultural awareness of Christian clergy:

"A modern priest or minister might be well schooled in the theology of Bultmann, Tillich, and Karl Barth and may be intimately familiar with the question of the Q document and its strata of composition, and yet find himself at a total loss when a parishioner has seen an angel."

Here Smoley touches on Western Christendom's tendencies toward emphasis on the rational elements of faith, on doctrine, and on the history of Christianity in the West, but its frequent inability to address the experiential elements, specifically within the contexts of the shift away from preferences for an institutionalized form of faith and toward a spirituality of quest with the increasing influence of Eastern and esoteric spiritualities. Such insights demonstrate that it is time for our seminaries and other Christian educational institutions to broaden their theological educational focus in light of changing cultural circumstances in order to address our shortcomings. It appears that we need to prepare less for educating chaplains in Christendom culture and instead prepare missional apostolic types for cultural engagement as well as pastoral care.

How can we explain the increasing interest in neo-Gnosticism, often more readily accepted than the institutionally and modernity connected Chrisendom? Smoley notes that the reasons are multiple and complex, but he states that one of the reasons seems to be perceived shortcomings and a loss of vitality in Christianity. He uses the illustration of an egg with the yoke and white sucked out of the inside leaving only the shell. While it still looks good on the outside, the inner vitality is gone and the remaining shell is fragile. Might the interest of growing numbers of Westerners in forms of neo-Gnosticism be due at leas in part to our failures to live out and put forward a robust form of the spiritual path of Jesus?

Finally, Smoley concludes the book with a discussion of faith, reason, and gnosis (inner knowledge). He interacts with the insights of Wouter Hanegraaff, a noted scholar of esotericism in the West. Hanegraaff states that Western civilization is rooted in the "three major impulses" of reason, faith, and gnosis:

"Reason holds that 'truth - if attainable at all - can only be discovered by making use of the human rational faculties, whether or not in combination with the senses.' Faith, by contrast, says that reason in itself does not provide us with ultimate answers, which can only come from a transcendental realm and are encapsulated in dogmas, creeds, and scriptures. Gnosis teaches us that 'truth can only be found by personal, inner revelation. . . .This 'inner knowing' cannot be transmitted by discursive language (that would reduce it to rational knowledge). Nor can it be the subject of faith . . .because there is in the last resort no other authority than personal, inner experience."

Hanegraaf notes that the scientific enterprise has valued reason, while institutional Christianity has valued faith, although these are not mutually exclusive categories and institutional category has valued faith within an epistemological framework that also places great value on reason . Hanegraff notes that gnosis has been much less valued. While I disagree with the characterization of gnosis in the quote above, opting instead for forms of inner experience that provide one but not the only means to truth, and which can to some extent be described and transmitted by discursive language, thus removing the gnosis-rationality dichotomy, I am sympathetic to the notion that Western Christianity has not valued inner experience, or a form of gnosis if you will, as much as it should. Might it be possible for missional and culturally engaged Christians to rethink and rework the relationship between reason, faith and a form of Christian gnosis? Perhaps if we can it will bring us closer to recapturing a more biblical form of faith, and put some of the substance and vitality back into the shell of Christianity.

Monday, August 14, 2006

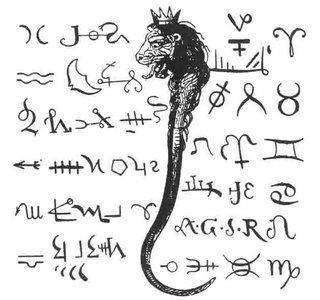

Morwics?: Religious Synthesis in Utah

When I heard the term “Morwics” in one of the Yahoo groups on alternative religions that I am part of I first thought of an alien race from a science fiction novel. But apparently the term refers to something very real in Utah, and perhaps beyond this state.

After relocating to Utah for seminary studies last year I learned about the small Pagan community in the state that lives among the dominant Mormon population. It seems that ex-Mormons not only gravitate toward evangelicalism and atheism as their religious choice options, but also toward Paganism. This makes sense in terms of a religious logic in that a rejection of what is considered a strict form of Christianity might lend itself toward identification with a variety of nature-based spiritualities such as Wicca.

What came as a surprise to me was to discover the existence of practicing Mormons who also practice forms of Paganism, resulting in the religious synthesis labeled “Morwics” by a Salt Lake City area practitioner of this spirituality. The claim is made that Morwics are a large and growing group whose interest in esotericism and magick has as its foundation early Mormonism’s interest in these areas as documented by researchers such as D. Michael Quinn in his book Early Mormonism and the Magic World View (Signature Books, 1998). I am working through my contact in a Yahoo group to talk to a leading Morwic in the near future to learn more about these folks.

Image source: http://altreligion.about.com/library/graphics/levi/solarserpent.jpg

Saturday, August 12, 2006

Hertenstein and Imaginarium: Christianity as Apollonian or Dionysian?

My friend and colleague at Cornerstone, Mike Hertenstein, who is a major creative force behind the Imaginarium, has written an article that is the substance of his seminar at this year's festival. It is titled "Why Should the Devil Have All the Good Bacchanals?," and it represents a fascinating discussion on myth, symbol, culture, Christian hsitory, and conceptions of the faith that raises the question as to whether Christianity should be understood as an Apollonian or Dionysian faith. This is a great article that discusses a fascinating topic covering ground from Carnival and Lent, to Dionysus and Apollo, to C. S. Lewis and Narnia. Enjoy, but as Mike notes in his article's subtitle, beware, "this is not a tame article."

Image source: http://www.culture.gr/2/21/211/21117a/00/lk17a013.jpg

Friday, August 11, 2006

The Feast of Fools: Theological Feasting on Festivity and Fantasy

One of the things I enjoy about reading the types of books that I do, and in engaging in a continual research process, is the discovery of various rabbit trails that take a research project and thinking into new and exciting areas. This happened recently with my studies for the Burning Man festival. One of the books I read, Brian Doherty’s This is Burning Man (Little, Brown and Company, 2004), recommended another book as a means of trying to understand this festival phenomenon. The book was The Feast of Fools (Harper Colophon Books, 1969). I found the title and the context of sacred festivity in which the book was recommended highly intriguing. When I went to Amazon.com to find out more about the book, I discovered the subtitle, “A Theological Essay on Festivity and Fantasy,” and I figured this was an important read. I ordered a used copy (for a steal at a mere forty-nine cents plus shipping) and after receiving it earlier this week (and balancing it out with my reading for the rapidly approaching Fall semester at seminary) I’ve managed to read the Overture, the Introduction, and the first chapter.

I hope to gain further insights and applications as I continue to read through the book and reflect on its wisdom. But from what little I’ve read so far the book seems to have application not only to Burning Man, as well as to the Imaginarium theme for 2006 which looked at cultural festivals related to death, and to broader questions of culture, festivity, and fantasy. The latter application was apparent with Cox’s discussion of the Feast of Fools celebration in parts of Europe that flourished during the medieval era, but which has largely died out, surviving only in vestigial form in events like Halloween and New Year’s Eve parties.

Cox believes that human beings are “essentially festive and ritual creatures,” designed for both the expression of festivity and fantasy, but for a variety of reasons this aspect of celebrating what it means to be human and spiritual has largely died out in the modern and late modern West. Western forms of Christianity may have played a part in this as Cox rightly notes that “Christianity has often adjusted too quickly to the categories of modernity.” This has included a heavy emphasis on the Protestant work ethic. Not a bad thing to be productive mind you, but at the same something in us as individuals and as a culture dies without equal time given to festivity and fantasy. At this juncture might we ask just where any robust sense of sacred festivity and fantasy is to be found within typical expressions of Western evangelicalism?

I am part way through Cox’s discussion of festivity in relation to the philosophical notions of the death of God in the West. Remember that this book was written in 1969 as the so-called “counter-culture” was in full swing. While the death of God movement has largely died itself with various forms of Christianity as well as Western esotericism and Eastern spiritualities filling the vacuum, Cox’s discussion of the death of festivity and fantasy in the 1960s is instructive for its continued impoverishment in the 21st century West. For example, Cox discusses the differing ways in which religious traditions approach religion, with the historical religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam representing historical religions, and others, such as Tibetan Buddhism representing so-called “non-historical” religions that emphasize “the recurrent fundamentals of life and nature – the wheeling stars, the changing seasons, birth, sex, death. They help man situation himself in the larger cosmic setting. Cox notes that both approaches to religion have their value and place, but that we are missing the critical "point of intersection" between these worlds of history and divine mileu, and “our distorted Western attitude toward history and history-making” needs the corrective provided by celebration through festivity. (Might Christians be reminded of our shortcomings here with the emphasis on nature and festivity in neo-Paganism, if after all the so-called "cults" are indeed in some sense the unpaid bills of the church?) One sentence stuck out as I read this section where Cox provocatively asks, “If God returns we may have to meet him first in the dance before we can define him in the doctrine.”

I’m looking forward to my continued journey through this book that will surely involve lots of highlighting, wrestling with new theological and cultural questions, and attempts at applying it to a contemporary spiritual and cultural context.

Image source: http://www.feastoffools-phxaz.com/feast%20of%20fools%20mask%20left.jpg

Tuesday, August 08, 2006

Pan's Labyrinth, Myth and Popular Culture

Guillermo Del Toro is a film director from Mexico. He has directed a number of horror and fantasy films, including Cronos (1992), Mimic (1997), The Devil's Backbone (2001), Blade II (2002), and Hellboy (2004).

Del Toro's latest project is the fantasy film Pan's Labyrinth, set for release in America on December 29, 2006. The Official Movie Website press release summarizes the film:

"PAN'S LABYRINTH is a fanciful and chilling story set against the backdrop of a fascist regime in 1944 rural Spain. The film centers on Ofelia, a lonely and dreamy child living with her mother and adoptive father; a military officer tasked with ridding the area of rebels. In her loneliness, Ofelia creates a world filled with fantastical creatures and secret destinies. With post-war repression at its height, Ofelia must come to terms with her world through a fable of her own creation."

I bring attention to this film not only because of my appreciation of the fantasy and horror genres, and my appreciation for the creativity and directoral work of Del Toro, but also because of mention of this film on WildHunt, a Pagan blog. WildHunt was intrigued by the film when it made its debut at Cannes due to Pagan themes within it. (We might also note that a remake of the classic 1973 horror film The Wicker Man that touched on Pagan themes is also in production.) The blog includes an excerpt of dialogue from the film that illustrates this element:

PAN: Me? I've had so many names...Old names that only the wind and the trees can pronounce. I am the mountain, the forest and the earth. I am...I am a faun. Your most humble servant, Your Highness.

This intersection between popular culture and religious studies is of great interest to me for a number of reasons.

First, as Western culture continues its journey in late modernity or postmodernity it seems as though fantasy is increasingly popular as opposed to science fiction in previous decades.

Second, various subcultures are drawing upon this interest in fantasy, whether evangelicals and other varieties of Christians through The Chronicles of Narnia, or Pagans with their interest in Pan's Labyrinth.

Third, although a number of film critic websites have praised Labyrinth, it has thus far received little attention on the radar screen of American pop culture.

Fourth, as the film release draws closer and its promotion increases it will be interesting to watch the response of some segments of evangelicalism. One website has already linked it with Satanism and pedophilia. But then again, it takes issue with the mythology within Narnia as well.

I'll try to be optimistic here in my hopes for evangelical engagement with popular culture with this films' release later this year. My hope is that American evangelicals will develop a more sophisticated form of engagement with myth, symbolism, religion, and culture than we have previously in the culture wars. I don't know that I should hold my breath.

Image source: http://www.twitchfilm.net/pics/pan_lab_6.jpg

Monday, August 07, 2006

Eugene Peterson and Relevancy of the Message

Many Christians in America and the West are familiar with Eugene Peterson. He is a prolific author who writes with a pastor's heart. He is perhaps best known for not only his writing on Christian spirituality, but also for his Bible paraphrase The Message. I recently came across a March 2005 interview with him in Christianity Today magazine. The interview addresses concerns over shallowness in American Christianity, and includes the following question by CT and the response by Peterson:

Many Christians in America and the West are familiar with Eugene Peterson. He is a prolific author who writes with a pastor's heart. He is perhaps best known for not only his writing on Christian spirituality, but also for his Bible paraphrase The Message. I recently came across a March 2005 interview with him in Christianity Today magazine. The interview addresses concerns over shallowness in American Christianity, and includes the following question by CT and the response by Peterson:As I read this portion of the interview I was struck by a sense of both agreement and disagreement with Peterson. Let me explain. I understand and share his concerns for the shallow approach to Christian living and spirituality by many Americans, no doubt a reflection of the shallow nature of many of our churches influenced by America's sense of rugged individualism and consumer culture. From this perspective in mind we certainly do not want to "gut" the gospel out of a desire for relevancy to a given subculture that ends up compromising the radical message of Jesus' Kingdom.What if we were to frame this not in terms of needs but relevance? Many Christians hope to speak to generation X or Y or postmoderns, or some subgroup, like cowboys or bikers—people for whom the typical church seems irrelevant.

When you start tailoring the gospel to the culture, whether it's a youth culture, a generation culture or any other kind of culture, you have taken the guts out of the gospel. The gospel of Jesus Christ is not the kingdom of this world. It's a different kingdom....

I think relevance is a crock. I don't think people care a whole lot about what kind of music you have or how you shape the service. They want a place where God is taken seriously, where they're taken seriously, where there is no manipulation of their emotions or their consumer needs.

Why did we get captured by this advertising, publicity mindset? I think it's destroying our church.

However, I disagree with Person in another sense. I wonder whether he has not confused all forms of communicating the gospel within culturally appropriate forms with compromise of the gospel. The biblical message and the history of Christian missions is filled with a number of examples of communicating the narrative of the missio Dei through and into the various cultures that the narrative encountered. While this may at times have been done in inappropriate ways as evidenced in the history of both Catholic and Protestant missions, missiologists have attempted to do so in a way that strives for a critical contextualization whch is faithful to both the essence of the gospel and cultural contexts. As Darrell Whiteman has noted in an article in the International Bulletin of Missionary Research 21:1 (January 1997), "Contextualization is not something we pursue motivated by an agenda of pragmatic efficiency. Rather, it must be followed because of our faithfulness to God.."

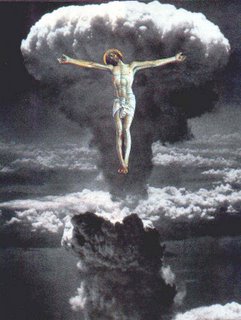

Cultures change regularly, and have done so in dramatic ways since Jesus walked in Palestine as graphically illustrated in the provocative "atomic Jesus" image that accompanies this blog post. And yet the ancient message of the gospel is important and relevant for people of the twenty-first century. But it must be communicated in ways that speak meaningfully and relevantly to differing cultural contexts. We seem to understand this in cross-cultural contexts overseas, especially through our support and endorsement of Bible translation projects. Peterson himself seems to understand this to some extent through his paraphrase of the Bible for contemporary Westerners. But communication of Jesus' message goes far beyond language and contemporary vernacular and embraces the totality of a culture or subculture's thought forms and lifeways, that includes but goes far beyond considerations of worship styles and music. Critical missional contextualization must not be confused with compromise, and is critical whether expressions of church take place in Africa or Los Angeles. If we forget these we have compromised the message.

Image source: http://desertpastor.typepad.com/paradoxology/atomic_christ.jpg

Tuesday, August 01, 2006

Burning Man, Sacred Space,...and Church?

What does a “counter-cultural” festival like Burning Man have to do with church and Christianity in America? Perhaps more than we might think.

Today I will be picking up some items to include in my survival gear for my attendance and participation in the 2006 Burning Man Festival coming up August 28 – September 4, with the theme Hope & Fear: The Future. I am going with a small group from two churches in northern California, including Fair Oaks Presbyterian Church and Shadowridge Church. The group is attending in order to learn about this interesting subculture, and to consider its ramifications for missions in their local church contexts. This is of interest to me as well, and my attendance also serves as my summer missions project for seminary study. In addition to my reading of academic and popular treatments on the festival, I will write a project paper that brings together my participant observation at the festival, the readings, and other studies I have done in the areas of anthropology of pilgrimage and culture. The paper will sketch the history and development of Burning Man and look at the missiological and ecclesiological implications of the festival.

But back to my original question that I began this post with: What does Burning Man have to do with church and Christianity in America? While it is often characterized by the media as little more than a place for adults to thumb their nose at authority and traditional expressions of Western culture, scholars have recognized the religious significance of the Burning Man experiment in intentional community. Sarah Pike of California State University, Chico has written that this religious significance is

“characterized by powerful ritual, myth and symbol; experiences of transcendence or ritual ecstasy; experiences of personal transformation; a sense of shared community; relationship to deity/divine power, and, perhaps most importantly, sacred space.”Most importantly, these characteristics take place in “an important cultural and religious site that exemplifies the migration of religious meaning-making activities out of American temples and churches and into other spaces.”

Pike concludes the introductory portion of her essay by stating that, “I want to suggest that popular religious sites like Burning Man festival are essential to an understanding of contemporary issues and future trends in American cultural and religious life.”

I think Pike is right, and my hope is that our experiences and research at Burning Man can bring helpful lessons to those in missional churches and the emerging church. I will post reflections and pictures here at the conclusion of the festival in early September as my schedule permits.

(Citations are from Sarah M. Pike, “The Burning Man Festival: Pre-Apocalypse Party or Post-modern Kingdom of God?,” The Pomegranate 14 (August 2000): 27-28. The essay was reprinted as “Desert Goddesses and Apocalyptic Art: Making Sacred Space at the Burning Man Festival” in Michael Mazur & Kate McCarthy (eds), God in the Details: American Religion in Popular Culture [Routledge, 2001].)

Image source: http://phillips.blogs.com/photos/uncategorized/410_burning_man.jpg. All Burning Man images are the intellectual property of Burning Man LLC.