This blog represents an exploration of ideas and issues related to what it means to be a disciple of Jesus in the 21st century Western context of religious pluralism, post-Christendom, and late modernity. Blog posts reflect a practical theology and Christian spirituality that results from the nexus of theology in dialogue with culture.

Wednesday, November 30, 2005

Missional Church in the Intermountain West Meeting

Next week I will post some thoughts on the results of the Missio.us meeting and Alan's presentation. Stay tuned for an electronic interview published here in the near future with Ryan Bolger of Fuller Seminary, discussing his new book with Eddie Gibbs on emerging churches.

A Loving Memory for a Beloved Son

Love,

Dad, Wendy, Joey and Jessica

Tuesday, November 22, 2005

If It Walks Like a Duck: Missions as Beyond Mere Self-Perception

For the last several years some colleagues and I have worked to articulate and model a new paradigm for response to new religions and alternative spiritualities, one that draws upon the insights of cross-cultural missions that have been used successfully in the history of Christian missions in cultural contexts around the world, but which is especially absent in the "Judeo-Christian" context of America. It has been interesting to see the responses to our work. Thus far they have largely positive, as evidenced by the book reviews given of Encountering New Religious Movements (Kregel Academic & Professional, 2004) by missions journals, periodicals, and even popular sources like Christianity Today. The only major criticism leveled thus far has come from those in countercult ministry, but even there we have some a small glimmer of hope. A few individuals and ministries have used the term "missions" in connection with their work among the new religions, and many view themselves as missionaries.

For the last several years some colleagues and I have worked to articulate and model a new paradigm for response to new religions and alternative spiritualities, one that draws upon the insights of cross-cultural missions that have been used successfully in the history of Christian missions in cultural contexts around the world, but which is especially absent in the "Judeo-Christian" context of America. It has been interesting to see the responses to our work. Thus far they have largely positive, as evidenced by the book reviews given of Encountering New Religious Movements (Kregel Academic & Professional, 2004) by missions journals, periodicals, and even popular sources like Christianity Today. The only major criticism leveled thus far has come from those in countercult ministry, but even there we have some a small glimmer of hope. A few individuals and ministries have used the term "missions" in connection with their work among the new religions, and many view themselves as missionaries.But it is not enough to merely perceive of oneself as a missionary. Missions extends beyond mere self-perception. At a minimum, a truly missional approach (as defined by the history of Christian missions and missiology) to new religions must include certain elements.

1. Missional attitudes. As was stated in the 2004 Lausanne issue group paper on postmodern spiritualities in this regard,

2. A cultural perspective rather than "cultic." In 1980 the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization issue group that addressed "mystics and cultists" recognized these groups as unreached peoples, an insight reaffirmed by Lausanne in 2004. In the increasingly postmodern West, individuals are defining themselves by their social networks that are often intimately connected to their spirituality. While we recognize the existence of unique beliefs within the the new religions, missional approaches to these groups and movements seek to move beyond belief as the defining and controlling factor in understanding and response. 3. Incarnational presence. Just as Jesus took flesh and lived out (as well as proclaimed) the gospel to the cultures of his time, the church has been given his example and command to follow in like manner (John 20:21). Missional approaches to new religions involve the development of ongoing, respectful, loving relationships as the foundation and context for sharing the gospel of the Kingdom. Monological proclamation at people falls short of the relational aspects within culture of missional approaches."An examination of the materials produced by many evangelical countercult apologists reveals an overwhelmingly adversarial and confrontational attitude to the New Spiritualities. This confrontational attitude seems more interested in defeating spiritual foes than lovingly walking life's journey with seekers in the New Spiritualities while seeking to incarnate the gospel. Evangelicals are encouraged to foster attitudes that facilitate service as ambassadors of Christ."

4. Application of cross-cultural missions methodology. Returning to the 2004 Lausanne paper once again,

"The development of an incarnational ministry necessarily involves certain processes of study and reflection about unreached people groups and how the gospel can be communicated effectively to them. Missiologists refer to these processes by the expression 'critical contextualzation.'I appreciate that some in the countercult think of themselves as missionaries, and their ministries as missional. However, self-perception is not always reality. We've heard the phrase before that if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, then it's a duck. To modify the phrase, if it walks like an apologist, and quacks heresy refutation, then its a countercultist, not a cross-cultural missionary. Missions involves moving beyond mere self-perception to the embrace and utilization of missional ways of being and acting.

"Contextualization involves communicating the gospel about Christ in a manner that enables people in specific cultural settings to truly and honestly grasp what the gospel is about and to experience the risen Christ within that culture."

Theological Engagment with Popular Culture: Surely We Can Do Better

The latest Harry Potter film hit the theaters last weekend, and it did very well financially, as throngs of Potter fans filled theaters across the country. But as with the previous films, and the books upon which they are based, a small chorus of evangelical voices have begun to complain, raising concerns of alleged evil and Witchcraft, creatively packaged as a means of desensitizing young people, opening doorways into the occult. (As an aside, I am not aware of similar concerns raised by Christians in previous generations with the magical framework and Witches in The Wizard of Oz, or the Wizard in The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad. It would make for a fascinating cultural study as to why the lack of concern then, but the uproar now.)

The latest Harry Potter film hit the theaters last weekend, and it did very well financially, as throngs of Potter fans filled theaters across the country. But as with the previous films, and the books upon which they are based, a small chorus of evangelical voices have begun to complain, raising concerns of alleged evil and Witchcraft, creatively packaged as a means of desensitizing young people, opening doorways into the occult. (As an aside, I am not aware of similar concerns raised by Christians in previous generations with the magical framework and Witches in The Wizard of Oz, or the Wizard in The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad. It would make for a fascinating cultural study as to why the lack of concern then, but the uproar now.)It will remain to be seen whether similar concerns will be raised with the December release of The Chronicles of Narnia. Typically, fewer evangelicals raise concerns over the magic of C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien, but assuming their arguments are valid in Potter contexts it would seem inconsistent not to apply it to fantasy written by Christians, but that's a big assumption. I am not encouraging critique of either of these authors. I am simply noting an inconsistency.

It is not my intention with this post to weigh in on the long-standing Potter controversy in conservative evangelical circles. Rather, I would like to make a few suggestions for how evangelicals might more positively engage popular culture.

1. Remember how stories function. One of the main arguments against Potter has been the alleged occultism and Witchcraft found in the books and movies. But before rushing to judgment it will be helpful for us to remember how stories function, whether in the form of literature or film, in drawing upon sources to tell their tales. C. S. Lewis stated that, "Within a given story any object, person, or place is neither more nor less nor other than what the story effectively shows it to be. The ingredients of one story cannot 'be' anything in another story, for they are not in it at all." (C. S. Lewis, "The Genesis of a Medieval Book," as quoted by Walter Hooper, C. S. Lewis: A Companion and Guide [HarperSan Francisco, 1996], 430.) With this important consideration in mind, it would seem that even if we grant that Rowling draws upon actual elements of Witchcraft and occultism in her stories, these elements take their meaning as they are defined by the author in the story, and it is a mistake to confuse them with their meanings outside the framework of the story.

2. Rethink evangelical engagement with popular culture. If one were to conduct a "person on the street" poll and ask the average person what evangelicals view positively in popular culture, I believe it would be a short list. We are known more by what we are opposed to rather than what we affirm. In response to popular culture evangelicals tend to either a) oppose it, b) ignore it, or c) create their own version of popular culture. I'd like to suggest another alternative, and that is a more positive and theologically balanced engagement with popular culture. Evangelicals whine and wring their hands over the success of things like Harry Potter, but whose fault is that? Where are the evangelicals incorporating creativity with their spirituality in our generation like Lewis and Tolkien did for previous generations? And we desperately need evangelicals with academic training in culture (including popular culture) and theology that integrates these disciplines in order to develop a practical theology for creative cultural engagement in the West in the twenty-first century.

As our culture continues to explore its fascination with story, image, and cinema, evangelical critiques of the type frequently directed at Harry Potter will exacerbate our increasing estrangement from popular culture. Let's rethink this thing and not dig our hole any deeper.

Monday, November 21, 2005

Jesus & Paul: Kingdom Community, Not Church Planting

Once in a while it's good to realize that I'm not alone in my thinking. I don't need to be vindicated, but it is comforting to know that I haven't completely lost my theological marbles.

Once in a while it's good to realize that I'm not alone in my thinking. I don't need to be vindicated, but it is comforting to know that I haven't completely lost my theological marbles.About a month ago I was on staff part time as an associate pastor in a church plant here in Utah. I was asked to preach a few times, and I like using such opportunities (including this blog) to push the envelope by being provocative in the hopes of stimulating fresh thinking among evangelicals and others. During one of my sermons I stated that in my view Paul was not a church planter. Despite what we often hear in the received wisdom, I said that Paul was primarily an ambassador announcing the Kingdom, and that a byproduct (if you will) of this herald and embodiment of the Kingdom was the formation of the church, but that Paul was not intentionally planting churches per se. (Incidentally, this and other perspectives were not well received by the pastor and I made the decision to pursue my theological and missiological deconstruction and reconstruction apart from being a part of this church's staff.)

Before you throw up your hands and say to yourself, "Morehead has definitely lost it," consider the fact that much the same perspective has been offered by others that the reader may be more willing to consider than my own. For example, I am currently enjoying the book Emerging Churches (Baker Academic, 2005) by Eddie Gibbs and Ryan Bolger, and in the book I was pleased to read the following:.

"Jesus was not a church planter. He created communities that embodied the Torah, that reflected the kingdom of God in their entire way of life. He asked his followers to do the same. Emerging churches seek first the kingdom. They do not seek to start churches per se but to foster communities that embody the kingdom....Jesus created an alternative social order, one built on servanthood and forgiveness, through the activities he performed as a leader of a counter-temple movement. Paul continued this model as well. 'If we stated the agenda of Paul's mission in modern terms, it seems clear that he was building an international, anti-imperial, alternative society embodied in local communities.'...missional communities differ greatly from current forms of church planting." (pp. 59-60)I agree, and their sentiments echo my own feelings on the issue. This assessment by a professor of church growth and a missiologist is worth considering. I hope that others will reassess other facets of theology, missiology, and ecclesiology with the challenges posed by the emerging cultures. The shifts in culture may provide us with an opportunity to recapture a more biblical understanding and approach.

Sunday, November 13, 2005

Understanding Before Critique: Let's Really Become Conversant with the Emerging Church

I recently became aware of a post in an Internet group of the countercult community. A post had been made sharing links with resources critical of the evangelical emerging church movement, and it stated that if one wants to see the effects of the emerging church on someone from the countercult to see my Blog. I contacted the person making this post through personal email to respond to problems with the post, and to share concerns about countercult (and some apologetic) critiques of the emerging church. A few of these thoughts are included here.

I recently became aware of a post in an Internet group of the countercult community. A post had been made sharing links with resources critical of the evangelical emerging church movement, and it stated that if one wants to see the effects of the emerging church on someone from the countercult to see my Blog. I contacted the person making this post through personal email to respond to problems with the post, and to share concerns about countercult (and some apologetic) critiques of the emerging church. A few of these thoughts are included here.First, I am no longer a part of the evangelical countercult community. While I have worked within this community in years past, I no longer utilize the paradigm and methodologies of this community, neither do I identify with them as a member of their community. Instead, I utilize an interdisciplinary, cross-cultural missions approach in the area of new religions and alternative spiritualities, and I consider myself a missionary and missiologist.

Second, it is inaccurate to say that I have been influenced (positively or negatively) by the emerging church movement. Over the last several years, I have been influenced by fresh reflection biblical studies, the history of Christian missions, anthropology, religious studies, the sociology of religion, intercultural studies, and most notably, missiology. This interdisciplinary perspective, with a primary influence coming from missions, has been the driving force behind my move from an apologetic to a missional paradigm (that also incorporates a culturally-relevant and intellectually rigorous apologetic element when appropriate) in the area of new religions. My study and work with the emerging church has likewise been influenced by these studies, but the emerging church has not colored my other areas of ministry.

Third, discerning and missional Christians should be very concerned by some of the criticism of the emerging church in the evangelical world. One aspect of it has been simplistic in its analysis, resulting in condemnation of the movement to the point of labeling it "a threat to the gospel," as seen in denunciations by Albert Mohler, and the Southern Baptists. The assessment and indictment by some in the countercult community is even more disturbing, including the simplistic and critical aspects of the previously mentioned critiques, as well as an unfortunate anti-Catholic element.

Perhaps more disconcerting, given his status as a scholar and the quality of his previous work, is the problematic critique of the movement of D. A. Carson. While I have the utmost respect for his scholarship in the area of his expertise, I fear that his latest work is a reminder of the dangers of straying from one's specialty. His book, Becoming Conversant with the Emerging Church Movement, is frequently cited by critics of the emerging church as if it were the definitive summary and critique. Carson's book does provide some criticisms worthy of consideration, but overall the book is flawed, both in its understanding of the emerging church, and in many of the concerns it raises. I refer the interested reader to a few sources that confirm my concerns. Eddie Gibbs recently wrote a brief review for Christianity Today that provides reflections from a church growth and missions perspective. Dr. David Mills wrote a good critique of the ideas presented in book from Carson's lectures at Cedarville. And Fuller missiologist Ryan Bolger has some good critical thoughts on the book found at his Blog. The point of reading these articles critical of Carson is to recognize that Carson's book is flawed and that it does not live up to it's title: its content was written by someone who was not truly conversant with the emerging church.

Fourth, the uncritical acceptance of Carson's critique by the countercult and some evangelical apologists demonstrates both the unfortunate willingness to accept that which confirms our immediate suspicions without careful analysis, and the all too common leveling of criticism before genuine understanding. I don't believe the emerging church represents "the answer" for the church in the Western world, but at least they are asking some of the right questions, and experimenting in response to cultural change. A successful church in the West will be found in a redisovery of and new commitment to the missio Dei, and I hope the emerging church places greater emphasis here in the near future. But regardless of one's view of the emering church, these movements deserve to be understood, appreciated, and critiqued fairly.

All of this causes me to wonder that if the "discernment community" has such serious problems in fairly assessing a movement within its own fold, how far can we trust their analysis and prescription for the challenge of new religions in the West?

For those interested in a new book that is now available via Amazon.com, I recommend a book co-authored by Eddie Gibbs and Ryan Bolger titled Emerging Churches: Creating Christian Community in Postmodern Cultures (Baker Academic, 2005). The book draws upon research in the U.S. and U.K., as well as the expertise and experience of the co-authors in the areas of missiology and church growth.

And check back with this Blog in December. Ryan has agreed to an electronic interview on the subject of emerging cultures, emerging church, and emerging spiritualities that will be published in installments here in the near future.

Friday, November 11, 2005

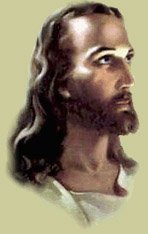

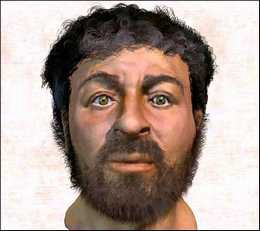

The Changing Face of Jesus

Growing up in northern California I remember a painting of Jesus that was hanging in the entry way of the church I attended for several years. It was one that is familiar to many American Christians, reflecting a European conception of Christ.

Growing up in northern California I remember a painting of Jesus that was hanging in the entry way of the church I attended for several years. It was one that is familiar to many American Christians, reflecting a European conception of Christ.

As I grew older and pursued biblical and historical studies I came to recognize that the face of Jesus looked very different. Jesus wasn't a blue eyed European, but as a Jew he had the Semitic features common to his ethnicity and period of history.

But as I study not only theology, but also the cultural and historical shifts in Christendom in the twenty-first century, I think we can see not only the changing face of Jesus, but related and identified with that, the changing face of the church as well. I just finished Jenkins' The Next Christendom, and the following quotes are relevant to the changing face of Jesus and the church, a face that challenges Christendom in the Western world, and most especially the Northern Hemisphere:

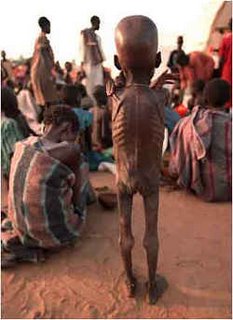

African and Latin American Christians are people for whom the New Testament Beatitudes have a direct relevance inconceivable for most Christians in Northern societies. When Jesus told the "poor" they were blessed, the word used does not imply relative deprivation, it means total poverty or destitution. The great majority of Southern Christians (and increasingly, of all Christians) really are the poor, the hungry, the persecuted, even the dehumanized. India has a perfect translation for Jesus' word in the term Dalit, literally "crushed" or "oppressed." This is how that country's so-called Untouchables now choose to describe themselves: as we might translate the biblical phrase, blessed are the Untouchables.I think I am beginning to see a new face of Jesus in the twenty-first century.

Knowing all this should ideally have policy consequences, which are at least as urgent as redistributing church resources to meet the needs of shifting populations. Above all, the disastrous lot of so many Christians worldwide places urgent pressure on the wealth societies to assist the poor. A quarter of a century ago, Ronald J. Sider published the influential book, Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger, which attacked First World hypocrisy in the face of the grinding poverty of the global South. The book could easily be republished today with the still more pointed title Rich

Christians in an Age of Hungry Christians, and the fact of religious kinship adds enormously to Sider's indictment. When American Christians see the images of starvation from Africa, like the hellish visions from Ethiopia in the 1980s, very few realize that the victims share not just a common humanity, but in many cases the same religion. Those are Christians starving to death. (Jenkins, 266-217)

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

Magick, the Supernatural & Re-Enchantment

I read the Wildhunt Blog today, a Blog that provides some interesting perspectives on spiritual issues from a Pagan perspective. The Blog recently posted some comments on magick and the supernatural, and in the process alerted me to an article by Peggy Flatcher Stack in The Salt Lake Tribune titled "Where faith, magic meet". The article contains a number of items worthy of consideration. Here's one brief but interesting quote:

I read the Wildhunt Blog today, a Blog that provides some interesting perspectives on spiritual issues from a Pagan perspective. The Blog recently posted some comments on magick and the supernatural, and in the process alerted me to an article by Peggy Flatcher Stack in The Salt Lake Tribune titled "Where faith, magic meet". The article contains a number of items worthy of consideration. Here's one brief but interesting quote:Today, some Christians shun magical fiction like Harry Potter and The Lord of the Rings or "The Matrix," fearing their allure will replace religious faith.Unfortunately I think the statement above is accurate, as the plethora of evangelical books, as well as website and newsletter articles condemning Potter, and Lord of the Rings demonstrate. With the forthcoming Narnia film in December this issue will take center stage once again, and may be accompanied by further articles and books expressing alarm at the magic of C. S. Lewis.

In the acceptance of a sacred-secular split in Western Christendom with the Enlightenment, and the resulting disenchantment of the world, did the church go too far in banning the "magical" activity of the Divine in the cosmos? With the postmodern emphasis on re-enchantment, can we rethink the place and extent of Divine activity in the creation that articulates a robust biblical worldview and properly distinguishes it from Pagan magickal ideas?

Tuesday, November 08, 2005

Further Thoughts on Syncretism: Future Battles Between North and South?

I received a lot of comments on the last post touching on syncretism. This is an ongoing issue of consideration for me, and I believe it will be an item of continuing concern over time with the global developments in Christendom.

I received a lot of comments on the last post touching on syncretism. This is an ongoing issue of consideration for me, and I believe it will be an item of continuing concern over time with the global developments in Christendom.As I mentioned in a comment in the previous post, Philip Jenkins, in his book, The Next Christendom (Oxford, 2002) discusses a shift in the number of adherents to Christianity globally from the Northern Hemisphere to the Southern Hemisphere. There are a number of important ramifications associated with this. Not only will Northern expressions of Christianity will be increasingly less influential in the global faith, but Northern Christianity will be challenged by the different expressions of the faith in the South, particularly in Africa, where independent churches "accept prophetic visionary ideas that have long since fallen out of fashion in the West" (p. 120). With the West's increasing awareness of Christianity in the South, the charge will likely be made with increasing frequency that "many Southern churches are syncretisitc, they represent a thinly disguised paganism, and all in all they make for a 'very superstitious kind of Christianity,' even 'post-Christianity'" (p. 121).

Jenkins goes on to point out that a more gracious assessment of this situation is possible, and that what is likely going on is the development of contextualized forms of the Christian faith, and a return to a more biblical worldview that does not entail the sacred-secular split found in Enlightenment-influenced Western Christianity. If for no other reason than to respond to increasing charges of syncretism by Northern Christianity aimed at the Southern Hemisphere, the issue of syncretism, and its relationship to contextualization and missiology, is a topic that needs to be put on a front burner and addressed in fresh ways in light of changing cultural circumstances. My hope is that if the Northern expressions of Christianity, including American evangelicalism, continue to decline in growth and influence, we can still resist a knee-jerk boundary maintenance response to the situation in the South, and instead, can assess the situation fairly and soberly in light of all the relevant data.

As I thought about the topic of syncretism lately I pulled a file on the topic and was reminded of my conversations with my Australian friend and colleague Philip Johnson. In his research that he passed along in 2004, he noted a few items worthy of our reflection, and hopefully, further spade work in research as well. I pass it along in the hopes of keeping the conversation, and our thinking, moving forward.

1. Etymology. Philip dug a little and noted that the term "syncretism" may have gone back to the Greek, and then later into French, and then into English. Key to our analysis here is how the term originated, and how its meanings and usages have changed over time in differing contexts.

2. Positive and negative. We might differentiate between constructive and destructive, or positive and negative syncretism. Although we usually think of the term in wholly negative ways in Western evangelicallism, some have recognized that all efforts at contextualization are in a sense syncretic. Indeed, the noted Scottish missiologist Andrew Walls has stated that Christianity is potentially the most syncretistic religion of all because of its willingness historically to engage its truth claims with indigenous cultures in terms of communication and inculturation.

3. Alternative terminology. The late New Zealand missiologist, Harold Turner, specialized in new religions in Africa and primal societies. He was associated with Leslie Newbigin, and was interested in missions in connection with "deep culture" rather than superficial cultural observances. He suggested that since "syncretism" has accrued such negative baggage in the West that alternative terminology might be considered. He proposed the term "synthetism."

4. Relationship to contextualization. The relationship between gospel and culture, ecclesiology and its expression in culture, is extremely important, particularly in light of changing global demographics between North and South. The ways in which the faith is expressed in and through local cultures, the dangers of the contextualization pendulum swinging too far into syncretism, and the opposite error of confusing genuine inculturation with syncretism, are key issues that must be considered in missiology.

5. Third World theologies. How will Christendom in the North respond to new theologies that will develop in the South? Will we recognize and accept our changing global and historical role and come alongside our Southern brothers and sisters in exploration and development of new theologies, or will be attempt to impose Western theologies and uncritically label new efforts as heresies?

A little poking around the Internet will also reveal some interesting gems that might provide some additional considerations, including the following:

Gerald Gort (ed), Dialogue and Syncretism: An Interdisciplinary Aproach (Eerdmans, 1989)

Andrew Walls (ed), Exploring New Religious Movements: Essays in Honour of Harold W. Turner (Mennonite Board of Mission, 1990)

Wednesday, November 02, 2005

Syncretism: Caution and Fear in Creative Contextualization and Theologizing

Evangelical fears of syncretism have surfaced in two separate instances in my experiences recently. In the first instance, a professor raised concerns about syncretism in connection with a cross-cultural missions approach by creative evangelicals in Australia who utilize tarot cards to share the gospel at Mind-Body-Spirit festivals.

Evangelical fears of syncretism have surfaced in two separate instances in my experiences recently. In the first instance, a professor raised concerns about syncretism in connection with a cross-cultural missions approach by creative evangelicals in Australia who utilize tarot cards to share the gospel at Mind-Body-Spirit festivals.In the second instance, a fellow seminary student shared concerns about syncretism in connection with class discussions on contextualizing the gospel in cultures, and in reassessing theologies in light of new historical and cultural considerations.

Syncretism is an important concern. Surely the gospel and expressions of Christianity have been compromised in cultures through inculturation that has been inappropriate. But contextualization and theologizing in cross-cultural contexts always runs the risk of syncretism. My concern is that evangelicals let their fears of syncretism prevent them from considering new approaches at contextualization in missions, and new theologizing, whether in cross-cultural contexts, or in reconsideration of cherished theological ssumptions in Western theology. Surely we need to consider the history of theology that has come before us, but has all the fresh thinking and activity already been done through creedal development and the Reformation? Or should the church in each generation be receptive to theologizing in light of cultural change, and fresh illumination by the Holy Spirit?