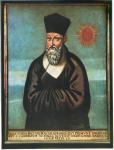

Matteo Ricci is one of the more fascinating figures from the history of Christian missions. Ricci, a Jesuit missionary to China, was the first missionary granted residency in the country after the previous missionary efforts of the Nestorians and previous Roman Catholics were destroyed in the fourteenth century. He continues to serve as a fine example of respect for culture, as well as the contextualization of the gospel and culturally relevant apologetics, and yet he is a figure that is largely unknown in evangelical circles.

Matteo Ricci is one of the more fascinating figures from the history of Christian missions. Ricci, a Jesuit missionary to China, was the first missionary granted residency in the country after the previous missionary efforts of the Nestorians and previous Roman Catholics were destroyed in the fourteenth century. He continues to serve as a fine example of respect for culture, as well as the contextualization of the gospel and culturally relevant apologetics, and yet he is a figure that is largely unknown in evangelical circles.Ricci was born October 6, 1552 in Macerata, Italy (interestingly the same year in which Francis Xavier died on China’s doorstep in Shangchuan Island). Ricci engaged in classic studies, and later studied law in Rome for two years. In 1571 he entered the Society of Jesus at the Roman College (now called the Gregorian University in Rome), with a program of studies that included philosophical and theological aspects, as well as mathematics, cosmology, and astronomy. The Jesuit emphasis on education would later be of great benefit to Ricci’s missionary work.

There are several important aspects of Ricci's work worthy of considerartion. The first was Ricci’s patience. He recognized that a successful mission would not happen overnight, and he was content to measure success as a process, and a slow one over a long period of time as well. Ricci recognized that a proper foundation had to be laid, and he was willing to invest the time and effort in appropriate ways in which to see a foundation set and appropriate work built upon it.

Ricci was also willing to devise an approach that was appropriate to the given cultural circumstances. After contrasting his understanding of Chinese culture with his previous experience working among Indian children in India, Ricci recognized that a different approach needed to be utilized. This was because of the highly literate nature of Chinese society compared to India, and the great number of religions that were present. Ricci recognized that China was not a blank slate, and that various cultural influences, including Chinese philosophy and religion, along with their view of cultural superiority, would all have to be considered in formulating an appropriate missions approach.

Another aspect of Ricci’s foundation was his focus on quality rather than quantity in terms of disciples. He set high standards for candidates receiving baptism, and did the same with discipleship as well. This approach caused problems initially, such as with Ricci’s insistence that one Buddhist official leave his concubines prior to baptism. As a result, one of the official’s spurned concubines engaged in a public protest of her treatment, even to the point of threatening suicide, but Ricci was unmoved. The woman did not follow through on her threats, and eventually, the official’s entire family became Christians.

Another foundational aspect of Ricci’s approach was an emphasis on strong interpersonal relationships:

Ricci believed in friendship as a chief virtue in itself, as well as the starting point for a successful presentation of the gospel. He learned the basic manners of Chinese high culture, and was careful not to offend his critics. When he disagreed, he did so in the most generous spirit possible. By contrast, the account of Gandhi, who recalls from his childhood how he could not endure some Christian missionaries who “used to stand in a corner near the high school and hold forth a Bible, pouring abuse on Hindus and their gods,” should make us think twice about the spirit of Incarnational ministry.A final foundational aspect of Ricci’s ministry was his desire to understand Chinese culture and the people within it as thoroughly as possible before he began sharing the gospel message. Those who have analyzed Ricci’s methodology have characterized it as a “person-centered, dialogical apologetic” and missional approach, one that sought to present the gospel to the Chinese through their culture in light of their beliefs, literature, and history. Ricci wanted to so immerse himself in Chinese culture that he could literally put himself in their thought world, and with this perspective he would be better prepared to communicate the gospel in culturally relevant ways.

Ricci’s accommodation principle on rites for ancestors was hotly disputed after his death. In 1651 a Roman Catholic official was sent to China by Rome to investigate the Jesuit practices influenced by Ricci in connection to the Chinese rites. Although Ricci’s acceptance of the ancestral rites for Chinese converts was supported by Decree in 1656, and later affirmed once again by the Jesuits in 1669, internal conflict within the Jesuit order and others within the Roman Catholic Church led to continued controversy. The Franciscans and Dominicans who entered China after Ricci’s death fueled an inter-order rivalry, and the controversy was not resolved until 1937. This incident is a somber reminder of not only the problems caused to missions by conflict of a political nature within a missionary community itself, but also that such matters are also fueled by disagreements over the relationship between theology and culture in the area of contextualization as well. It seems that current disputes over contextualization practices are not new and have historical precedents.

Three positive aspects stand out in Ricci's approach as most noteworthy:

1. Respect for and understanding of culture. As discussed above, Ricci had a great respect for Chinese culture, and he sought to understand it as thoroughly as possible before engaging it in proclamational form as a missionary. We would do well to emulate him here. The disciplines of sociology, religious studies, and missiology teach the careful student to develop an emic or insiders perspective on a culture and to strive to understand a culture as a member of that culture would understand it. Only then is it permissible to step outside this frame of reference in order to view it from the etic or outsiders perspective. In this writer’s opinion, in general evangelicals in ministry to new religions in the West spend precious little time developing a careful, sympathetic, empathetic, and respectful understanding of these spiritual and religious cultures. As one writer commented on this aspect of his work, “It has been over 400 years since Ricci set foot in China. One of his endearing legacies for the Evangelicals today is the lesson on missionary’s attitude of patience and respect for the other culture, expressed in attentiveness and learning.”

2. Emphasis on relationships. As noted earlier, Ricci valued relationships, and worked hard at developing them, even going so far as to write a book on the topic. This resulted in the establishment of several key relationships that served Ricci’s mission among the literati well.

Human beings are valuable to God in that they reflect the imago Dei. Relationships are an important aspect of what it means to reflect the divine image, and they should b sought in and of themselves as one image bearer seeks to interact with another as a valid activity in and of itself. Beyond this, relationships are also valuable to a missional way of being in discipleship. While an inappropriate emphasis on relationships can be problematic for the missionary, such as when the relationship does not serve as a vehicle to communicate the gospel, relationships must be understood as a vital aspect of the missionary venture. Missions in America is still recovering from its modernist tendencies toward impersonal forms of evangelism, whether by mass crusades or direct mailings and the like, and a rediscovery of the significance of relationships for missions must be a high priority, particularly for missions to new religious subcultures.

3. Contextualization. Ricci drew upon his extensive respect and knowledge of Chinese culture to communicate the gospel in various ways that would speak meaningfully within the cultural context of the Chinese literati. Although some critics have accused Ricci and later Jesuits of creating a “Christian-Confucian syncretism,” and even labeling Jesuit missions in China as “trickery, deception and expedience,” this is an unfair indictment of largely sound missiological efforts. The Jesuits were often pioneering in their appreciation of cultures, and it was the desire of Ricci and the Jesuits for an indigenous Christianity to take root that would survive over time.

Ricci’s example in contextualization points the way forward for the next generation of Christian mission in America and the West.

2 comments:

Hi, I thought you article on Matteo Ricci was extremely interesting. I am in the process of writing an essay on Ricci and was wondering what books/authors/readings you would suggest? Some of the quotes in your essay were very relevant to what I am doing, and I wondered where exactly they came from?

If you send me an email I'd be happy to send you the article I wrote as a seminary topic on the subject from which this post was excerpted and adapted. The paper includes the footnotes and a bibliography.

Post a Comment