As I have mentioned previously, I recently returned from Cornerstone Festival where I was privileged to participate in two seminar venues as a speaker. I will be posting some summary reflections here, and today I will begin with some thoughts on Imaginarium and their 2006 theme of "Days of the Dead."

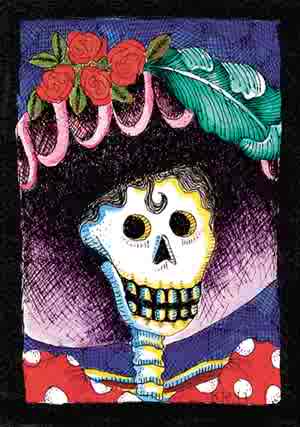

A couple of years ago I was asked to speak in the Imaginarium on the topic of anime, popular culture, and spirituality, an area of great interest to me as part of the overlap between theology, spirituality and popular culture. Earlier this year I participated in a series of email exchanges and discussions with Mike Hertenstein who's creativity, along with Dave Canfield, results in the Imaginarium program each year. (See Mike's post-Imginarium report here.) The 2006 theme sought to engage aspects of differing cultures as they grapple with death through festivals, symbolism, ritual, and popular cultural elements as well, such as film and literature. My meager contribution to this year's intellectual and artistic synthesis was a three-part cross-cultural look at North American Halloween and the Mexican Dia de los Muertos or the Day of the Dead.

In the first session I traced the historical and cultural origins and development of Halloween, from its earliest antecedents in Pagan Samhain as an agricultural and mythical festival, to the influence of Catholic All Souls' and All Saints' Day, to its continued development in North America as a form of public pranking and significance in courtship rituals expressions in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As Halloween continued to develop in response to the cultural and subcultural contexts of America, it eventually became influenced by popular culture, particularly in the 1970s through the horror film genre. Today it is increasingly popular, and functions as a means for children and adults alike to engage in costuming, identity exploration, and social inversion, existing largely as a secularized and consumer driven pop culture phenomenon far removed from any religious or spiritual aspects of previous Pagan influences.

My second session noted that the Mexican Day of the Dead is very different. This is a deeply religious celebration with some similarities to Halloween in the form of costuming, street requests for sweets and foods, and engagement with issues related to death, but the differences far outweigh the similarities. Celebrations include the making of sweets and special foods (such as "Bread of the Dead" and sugar skulls), the creation of family altars for the dead, and visits to grave sites. For Mexicans the Day of the Day is a marker of ethnic identity which encompasses festival, symbol, and ritual as a means for families and communities to both mock death and embrace it as a reality of life while also facilitating the continuing bond between the living and deceased ancestors.

My third session brought a three-part concluding analysis. This included noting that many evangelical and fundamentalist Christian portrayals of Halloween focus on the Pagan historical influences through Samhain while ignoring other influences, and a process of cultural development and modification in the holiday over time. In addition, I noted that conservative Christians also demonstrate faulty reasoning in their analysis of the holiday with simplistic formulas such as "Pagan influence = occult = off limits," or "horror film pop culture influence = occult = off limits." As to the first formula, not everything that comes from Pagan cultures should be dismissed as negative (in this case the Christian devil is too big, God too small, and Pagans too evil). In the second formula, it is inappropriate to dismiss a broad genre with sweeping labels. In both of these formulas some conservative Christians are quick to dismiss Halloween as "occultic" demonstrating a serious lack of understanding of both Western esotericism, Pagan cultures, and popular culture as well. For these and other reasons I believe the evangelical and fundamentalist critique of Halloween often misses the mark.

The third session also offered a contrast of Halloween and the Day of the Dead in North American and Mexican cultures. I noted that in America the Halloween celebration functions on a superficial level in the culture in ways that entertain aspects of popular culture from an individualistic perspective as participants engage in costuming and identity play. But the secular Halloween celebration really does not deeply and meaningfully engage death. By contrast, the Mexican Day of the Dead provides a religious festival for individuals and the culture to engage the reality of death and the continued connection of the living and the dead through a rich reservoir of symbol and ritual. It would seem that North Americans can learn a lot from our neighbors to the South in terms of cultural festivals.

A highlight of the Imaginarium was an evening celebration of Cornerstone's version of the Day of the Dead. Authentic sugar skulls from Mexico were passed out to participants, along with pens and labels, and people were given the opportunity to write the name of deceased loved ones and friends on them before placing them on the ofrenda or altar as a way of memorializing and expressing our continued connection with the dead. When this event was planned there was no way to know what the response would be, but as this portion of the night continued more and more people came forward to remember their loved ones through this ritual. Some were deeply touched emotionally, demonstrating a serious shortcoming in the American way of dealing with death (including the way we respond in our churches), and the value of learning from the festivals and rituals from of cultures.

I was privileged to be able to be a part of this year's Imaginarium. While a few brethren of the ultra-conservative variety found it necessary to pass out tracts decrying the Imaginarium's Days of the Dead theme, and a few also found it necessary to engage in a "mission trip" to Cornerstone, these folks were the minority, and their perspective and efforts demonstrate three things. First, as Lint Hatcher writes in his booklet on Halloween such folks are obviously missing the "spooky gene" which enables some of us to entertain a robust Christian faith while also enjoying aspects of Halloween and horror fandom. (I don't have the "Nascar gene" or the "country music gene" anymore than others have the "spooky gene," so perhaps we should appreciate our pecular genetic makeup and diversity rather than pointing fingers of disgust and sounding the alarms of heresy.) Second, while concern over evil is commendable an undue focus on such things ends up crossing the line from sound discernment to zealotry and boundary maintenance. Third, one of the reasons why Imaginarium explored this theme was to explore how evangelicals are missing out on important aspects of what it means to be human. In our knee-jerk Reformation reaction against ritual and symbolism we are missing important aspects of expression, not to mention a lot of fun. In the process we end up missing out on participating in the fullest dimensions of the human experience, and we deny the full implications of the incarnation. The Word came in the flesh to live among us and to participate in culture, including its ritual and symbolism. Evangelical overemphasis on the rational and the textual ends up denying the fulness of the incarnation that also embraces the imagination.

Image sources: http://www.faustosgallery.com/deaders/paperskulls/02b.jpg and http://www.azcentral.com/ent/dead/images/lacatrina.jpg

2 comments:

Thanks for your comments John. I think this shows a deeper look at the intent of the event (better than Lint's defense on the Slice blog).

I posted this comment on Jesus' use of paganism and death on the Slice blog and thought it might add some insight.

There seems to be some interest in Cornerstone using Scripture to defend their actions. While I can't defend their actions for them, I would like to point out some Scripture here about Jesus' use of pagan (maybe occult) culture in his ministry.

In Matthew 16:12-20 Peter makes his Good Confession that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God. He does this on a field trip to Caesarea Philippi, a pagan woship site for the god Pan. The sex cult was still active here, and their were still rumors of practices like child sacrifice.

Why would Jesus take Jewish followers, who even considered it unclean to enter such a city to such a place for the most important conversation of their lives? I think it was because he wanted to make a direct challegne to paganism and death. He made use of this evil place to add context to the radical and dangerous nature of his identity (which Peter was confessing), even going so far as to mention the "Gates of Hades" in his blessing in response to Peter's confession -- referencing the city's caves that some thought were an entrance into the Greek underworld. Jesus is announcing a daring challenge against death and the pagan system that would have caused his followers to tremble a little in fear. And so they should.

Now, what does that have to do with anything here? Well, Xians should not in anyway act as if the pagan world and death do not exist. They do and everyone else knows it. Too often we ignore the dark power in the pagan world and shelter our children from it so much that they are drawn to it when they have freedom. We lack a true spirit of encountering and overcoming the pagan. Also, sometimes we gloss over the problem of death with our rosy thinking. Americanism, combined with our faith, somtimes over emphasizes "never grow old" and the afterlife as the fountain of youth. We need to re-examine the reality of death.

Now, that being said, we should also not loose Jesus' tone of confrontation and conquest in regards to paganism and death. He came to promote a Kingdom that trumps all others. The implication is that, while it is not wrong to lead Xians to encounter paganism and death, our intent should always be to do so in a way that annouces Christ's victory.

Based on these reflections, those who were actually at the event can judge whether or not this was done.

John,

Thanks for your post and for noting the role the evolution of festivals go through in culture as they're reworked through subsequent generations.

I've put forward one or two ideas about how we can make use of Halloween in my context - even though it is not a notable celebration where I come from. I'd love to hear some of your comments.

Post a Comment