I have been struck in the past by God's dealings with Pagans as recorded in the Old and New Testaments. In my Old Testament class at seminary we recently went through Genesis and Exodus, and I was reminded of God's dealings with Abraham and Jethro while they were still in Paganism. While little information is available for in-depth study, it appears as if God related and reveald Himself from within their cultures and drew upon elements of those cultures, including their Pagan religion.

I have been struck in the past by God's dealings with Pagans as recorded in the Old and New Testaments. In my Old Testament class at seminary we recently went through Genesis and Exodus, and I was reminded of God's dealings with Abraham and Jethro while they were still in Paganism. While little information is available for in-depth study, it appears as if God related and reveald Himself from within their cultures and drew upon elements of those cultures, including their Pagan religion.This has caused me to reflect further on the relationship between culture and religion, and how this relates to God's dealings with Pagans in the past, as well as how this might relate to the present. I know that to raise the kinds of issues and questions that will come as a result of this post, especially the quote I will include below, is to invite questions and concerns about my orthodoxy, but I would ask my readers to refrain from judgment in order to ponder important questions.

I've mentioned Christian anthropologist Charles Kraft in a previous post. His book Christianity in Culture: A Study in Dynamic Biblical Theologizing in Cross-Cultural Perspective (Orbis, 1980), is thought provoking in the araes of culture, and cross-cultural theologizing. I present the following quote for creative contemplation:

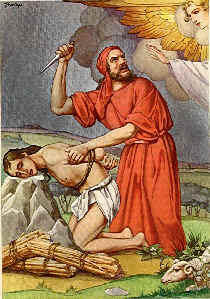

"Paganism is, according to Maurier [Maurier, Henri. 1968. The Other Covenant: A Theology of Paganism. New York: Newman Press], the point at which God starts his saving process. Maurier claims that paganism has today enough information in it, as it has ever had, so that the addition of the proper communicational stimulus, can lead people to saving faith in God through Christ. Paganism thus, in some sense, stands in continuity with the Christian Gospel. We have usually assumed discontinuity and antagonism between Christianity and paganism. Yet it was within paganism that God stimulated Abraham (and countless others whose stories are not recorded in the Bible) to faith based largely on the knowledge they already possessed. In the Old Testament mention is made of a few of those outside Israel who apparently came to saving faith. Among them were Melchizedek (Gen. 14:18; cf. Ps. 110:4; Heb. 7)), Abimelech (Gen. 20), Jethro (Exod. 3), Balaam (Num. 22-24), Job, and Naaman (2 Kings 5). These came within paganism rather than within Israel to the same faith-allegiance to the true God that those saved within Israel experienced. In the New Testament, too, we get a glimpse of such a possibility when, in Acts 18:24-19:7, we see that there were roving bands of John the Baptist's disciples making converts without, apparently, even having heard of Jesus.In light of Paganism in the Western world we might modify Kraft's question slightly. Not only are there Pagans who may never have heard of Christ at all, there are those who have heard of the all too common evangelical caricature of Jesus rather than the robust biblical Christ of the New Testament witness. (For those wondering what the differences might be see N. T. Wright. 1999. The Challenge of Jesus: Rediscovering Who Jesus Was and Is. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.) Might contemporary Pagans in the West be B.C. in the sense of having rejected a misunderstood and caricatured Jesus rather than the biblical Jesus who has been communicated appropriately within their cultural contexts? And how does God's workings with Pagans in the Old and New Testaments from within their cultures, including their Pagan religions, inform our understanding of, relationships with, and theologizing among contemporary Pagans? Are the Old and New Covenants even the appropriate starting place for such questions, or should we back up to God's revelation in creation and imago Dei?

"If the message and method are the same today as they were in biblical times, we must ask the hard questions concerning the necessity of the knowledge of Christ in the response of contemporary 'pagans.' Can people who are chronologically A.D. but knowledgewise B.C. (i.e., have not heard of Christ), or those who are indoctrinated with a wrong understanding of Christ, be saved by committing themselves to faith in God as Abraham and the rest of those who were chronologically B.C. did (Heb. 11)? Could such persons be saved by 'giving as much of themselves as they can give to as much of God as they can understand?' I personally believe that they can and many have."

No comments:

Post a Comment