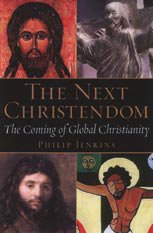

In a previous post I mentioned my appreciation of the work of Philip Jenkins. Jenkins is Distinguished Professor of History and Religious Studies at Pennsylvania State University. Jenkins is the author of a number of books, and previously I enjoyed his Mystics and Messiahs: Cults and New Religions in American History (Oxford University Press, 2000), and most recently I read his book The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2000) for my History of Christian Missions class at Salt Lake Theological Seminary.

In a previous post I mentioned my appreciation of the work of Philip Jenkins. Jenkins is Distinguished Professor of History and Religious Studies at Pennsylvania State University. Jenkins is the author of a number of books, and previously I enjoyed his Mystics and Messiahs: Cults and New Religions in American History (Oxford University Press, 2000), and most recently I read his book The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2000) for my History of Christian Missions class at Salt Lake Theological Seminary.Jenkins’ work in The Next Christendom raises serious questions for the church in the West, particularly in the areas of missiology, contextual theologizing, and the issue of syncretism. I contacted Dr. Jenkins and he graciously made time to provide brief answers to a few questions.

Morehead’s Musings: In the book The Next Christendom, you describe the shift in Christianity from the Northern to Southern Hemisphere, and then describe an expression of Christianity in the South that emphasizes visions, dreams, healings, ecstatic experiences and the like, a form of Christianity that has much more in common with a biblical worldview than a Western one influenced by the Enlightenment and modernity. Has the growth and forms of the Southern Church been recognized much in the North, and if so or when it does, how do you think it will be received?

Philip Jenkins: Briefly, we see things not as they are, we see things as we are – that is, people tend to see what happens in the global south to the extent that it meets our desires and expectations. Liberals see what they like in the south, conservatives as well, and both wonder how to use these trends for their own purposes. I would argue though that both sides are going to be disappointed. Yes, southern churches often are "fundamentalist" in their approaches to scripture. Yet readings that appear intellectually reactionary do not prevent the same believers from engaging in social activism. In many instances, biblical texts provide not only a justification for such activism, but a command. Deliverance in the charismatic sense can easily be linked to political or social liberation, and the two words are of course close cognates. The biblical enthusiasm we so often encounter in the global south is often embraced by exactly those groups ordinarily portrayed as the victims of reactionary religion, particularly women. Instead of fundamentalism denying or defying modernity, the Bible supplies a tool to cope with modernity, to allow the move from traditional societies, and to assist the most marginalized members of society. The message – the south will define itself in its own terms.

MM: In your book you state that the charge will likely be made with increasing frequency that “many Southern churches are syncretistic, they represent a thinly disguised paganism, and all in all they make for a ‘very superstitious kind of Christianity,’ even ‘post-Christianity’” (p. 121). How would you see popular evangelicalism responding to Southern Christianity?

Jenkins: Evangelicals in the north are so grateful to see the Christian expansion in the south that most are tolerant of slight deviations. But anyway, I would stress that the charges of syncretism are really overblown. When you ask Africans, say, where they get all these strange ideas about exorcism, dreams, etc., they point immediately to the book of Acts, rather than to ancient survivals of paganism, and they are quite right to do so.

MM: How will Christendom in the North respond to new theologies that will develop in the South?

Jenkins: I quote Joel Carpenter, “Christian theology eventually reflects the most compelling issues from the front lines of mission, so we can expect that Christian theology will be dominated by these issues rising from the global south.” He also notes how, facing the challenges of secularism, post-modernity, and changing concepts of gender, Euro-American academic theology still focuses “on European thinkers and post-Enlightenment intellectual issues. Western theologians, liberal and conservative, have been addressing the faith to an age of doubt and secularity, and to the competing salvific claims of secular ideologies.” Global south Christians, in contrast, do not live in an age of doubt, but must instead deal with competing claims to faith. Their views are shaped by interaction with their different neighbors, and the very different issues they raise: Muslims and traditional religionists in Africa and Asia, not to mention members of the great Asian religions. Accordingly, “the new Christianity will push theologians to address the faith to poverty and social injustice; to political violence, corruption, and the meltdown of law and order; and to Christianity’s witness amidst religious plurality. They will be dealing with the need of Christian communities to make sense of God’s self-revelation to their pre-Christian ancestors.”

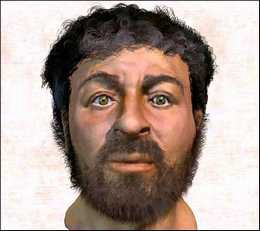

And this is a process that has often happened in the past, not least when Christianity spread into medieval Western Europe. To take one critical example, modern western interpretations of the atonement (both Catholic and Protestant) can be traced to the writings of Saint Anselm around 1100. For Anselm, human sins were like grievous offenses committed against a great lord, debts that required a ransom or restitution of great price, in the form of the death of God’s son. Though Eastern Orthodox theologians rejected this theory as over-legalistic, it made excellent sense to a western society deeply sensitive to questions of honor, fealty, seigniorial rights, and acknowledging the proper claims of lordship. The lord became a feudal lord. European Christians reinterpreted the faith through their own concepts of social and gender relations, and then imagined that their culturally specific synthesis was the only correct version of Christian truth.

MM: Will we recognize and accept our changing global and historical role and come alongside our Southern brothers and sisters in exploration and development of new theologies, or will we attempt to impose Western theologies and uncritically label new efforts as heresies?

Jenkins: I can answer that easily: yes, yes and yes!