Dr. Douglas Cowan is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies and Social Development Studies at

Renison College/University of Waterloo, where he specializes in “cults,” sects, and new religious movements, as well as religion on the Internet and religion and film. He is a co-general editor of

Religion Online: Finding Faith on the Internet (Routledge, 2004), and (with Jeffrey K. Hadden)

Religion on the Internet: Research Prospects and Promises (JAI, 2000). He is the editor-in-chief of the

Religious Movements Homepage Project, located at the University of Virginia. Dr. Cowan has also written several books including his most recent,

Cyberhenge: Modern Pagans on the Internet (Routledge, 2005).

Perhaps his most controversial book, however, at least among a segment of the evangelical community known as the “countercult movement,” is

Bearing False Witness? An Introduction to the Christian Countercult (Praeger, 2003). In the study of new religions and those who respond to them, scholars have examined the secular anticult movement, but few have distinguished between this and the evangelical countercult movement. I and my fellow co-editors of

Sacred Tribes believe that

Bearing False Witness? presents an important thesis, as well as criticisms of evangelical countercult methodologies worthy of careful consideration. For this reason we are pleased that Dr. Cowan has agreed to participate in this interview. Due to the length of the interview it will be posted here in installments, and the complete interview will be available in a future edition of

Sacred Tribes journal.

MoreheadsMusings: Dr. Cowan, thank you for participating in this interview. As we begin, please share some of your background with us. What led you into religious studies from the perspective of sociology of religion?

Douglas Cowan: Thanks for the opportunity. I do appreciate it. As I tell my students, I am something of a mixed bag in terms of my training and experience in Religious Studies. If a colleague has a BA, MA, and PhD in History, for example, and that makes her a purebred, I’m a reasonably well-mannered junkyard dog. I have a Bachelor’s degree in English Literature, a Master of Divinity, for which I specialized in Church History—I wrote my thesis, which became my first book, on The Cloud of Unknowing, a fourteenth-century English mystical text—and I have a PhD in Religious Studies. The benefit of this kind of multidisciplinary preparation is that I tend not to see things through any one particular disciplinary lens. Though I tend to function now as a sociologist of religion, both professionally and intellectually, I still bring a multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary approach to everything that I do.

I am also an ordained minister in the United Church of Canada, and served congregations in southern Alberta for a number of years before going to grad school for my doctorate. I spent two years training as a spiritual director—which was not my calling at all, by the way. Those experiences, as much as anything else, gave me the impetus for grad school by providing me with a topic I was passionate about researching—the evangelical Christian countercult. Since then, as you noted in your introductory material, in addition to the countercult, I have published on conservative reactionary movements in mainline Protestantism, religion on the Internet, and I am currently working on my second book on contemporary Paganism. John, I know you are also particularly interested in another ongoing project:

Sacred Terror: Religion and Horror on the Silver Screen. Since I bore easily, I tend to work on a lot of things at the same time.

MoreheadsMusings: How did the countercult community come to your attention as distinguished from the secular anticult movement, and why did you decide to research this movement?

Douglas Cowan: I really wasn’t aware of any of it until I was ordained and settled on my first pastoral charge. I mean, I grew up in the 1960s and 1970s and had been told that there were these dangerous, devious organizations called “cults” out there, but I had no real clue what that meant. Or even if it was true. Though I certainly wouldn’t consider them a “cult,” while I was an undergrad in Victoria, I did once get into a letter-writing campaign with a Jehovah’s Witness, the kind of tedious, minutiae-driven, micro-hair splitting debate you see in countercult apologetics all the time—“Is

eimi in John 8:58 present tense or a past participle or a present progressive or whatever, and, more importantly, why what you believe about it makes you a heretic.” That sort of thing. I found it a completely unfulfilling experience, a rather sad chapter in my life, actually. We were speaking different languages, were not going to see eye-to-eye, and that became clear almost immediately. However, several years later, having survived seminary, I figured I’d had all my theological shots and felt relatively immune to whatever the real world had to offer.

In my denomination, new ordinands are “settled” on a pastoral charge. Though you have some input into the decision, the Church essentially decides where you will serve first. When I got the call from the settlement committee, I was at my parents’ home on Vancouver Island.

The chair of the settlement committee called up and said, “We’re thinking of Cardston and Magrath for you,” two small towns in southwestern Alberta, just north of the Montana border.

“OK,” I replied, “I know where it is on a map. Tell me about it.”

“Ummm, well, how do you feel about inter-faith dialogue?”

“Fine... why?”

“Well, there are some Mormons there.”

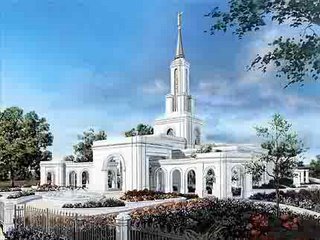

Cardston, you see, was settled in the late 1880s by Latter-day Saints who were leaving Utah after the passage of the Edmunds and Edmunds-Burke Acts—the anti-polygamy laws—and who were seeking a place where they could practice their religion free from state interference. In fact, the town of Cardston is named for one of Brigham Young’s sons-in-law, Charles Ora Card. In 1923, the Cardston saints dedicated the first LDS temple in Canada, the only one until the Toronto temple was dedicated in 1990. When I moved to Cardston, there were about five thousand people in the town, a little more than four thousand of whom were Latter-day Saints.

And I had the United Church. Since I knew very little about Latter-day Saints, I went to the Christian bookstore in my hometown and asked what they had on Mormonism. “Oh, we have the best book on the market,” the clerk replied, and handed me a copy of Ed Decker and Dave Hunt’s

The God Makers. I took it home and read it that afternoon. About three-quarters of the way through, though, I looked up and said, “Mom, they’re sending me to Mars.”

What I discovered when I got to Cardston, of course, is that Latter-day Saints are pretty much like everyone else. In fact, over the years I was there, they were extremely gracious in offering their ward facilities—which were obviously the largest in town—when we had, for example, a funeral that our tiny church could not accommodate. When my first book came out, the one on

The Cloud of Unknowing, the owner of the local LDS bookstore was quick to order ten copies—at a significant loss to him, I’m sure! When I left Cardston, the United Church had grown to the point where they were building a new church, and the Latter-day Saints pitched in on a number of occasions to help them do it.

Through all of this, I began to wonder about the disconnect—what as a sociologist of religion I would now call the “cognitive dissonance,” the difference between expectation and experience—between what I read in Decker and Hunt, and what I encountered living in the heart of Mormon Alberta for five years. At one point, I mentioned

The God Makers to someone, and he replied, “Oh, that’s just Christian hate literature.”

And I realized he was right. I began looking deeper into the socio-literary iceberg of which

The God Makers was only the tip and discovered this whole evangelical subculture dedicated to little more than countering the “cults.” I began to collect material, as much of the literature of the countercult as I could find, thinking it might make an interesting book someday. I collected backsets of

Saints Alive in Jesus Newsletter,

The Berean Call,

Christian Research Journal, and so forth. I haunted used bookstores for anything and everything I could find—which amounted to quite a collection, as everyone who has helped move my library can attest!

When I moved to Calgary in 1994, the University of Calgary was just starting its regularized doctoral program. I approached Irving Hexham, at that time probably the most knowledgeable person in Canada on new religious movements, and asked if he would be willing to supervise my work. He was, and I was admitted in the first intake to the program. I am also the first graduate of that program.

I knew that in my doctoral work I wanted to write about the evangelical countercult, but at first, to put it crudely I was simply interested in “proving them wrong.” As one reviewer of

BFW? noted, not infrequently, exposing the “soft underbelly” of countercult polemics is absurdly easy. I mean, so many of the arguments put forth by countercult apologists and polemicists are so obviously flawed, so logically inconsistent, and in not a few cases, so patently falsified, that in many cases it’s a wee bit like dynamiting trout. Interesting the first couple of times you do it, perhaps, but unfulfilling in the long run.

Irving pushed me to explore the topic more deeply, to understand the “why” of the countercult, not just the “what” and the “what’s wrong.” This is not an uncommon experience for beginning graduate students. They think they know what they want to do, until they realize there are so many more interesting questions to be asked. Which is why I moved to an analysis based on propaganda theory and a sociology of knowledge. I moved from trying to “get them” to trying to understand the motivations and the methods, the theological underpinnings and the sociological pressures that drive the countercult engine.